The Clandestine Press in the Great War

When the Germans invaded Belgium in 1914, very few Belgian newspapers succeeded in bringing their printing presses to a place of safety. Most journalists chose not to submit to censorship and stopped their activities. Nevertheless, the press, i.e. the censored press, remained the principal information and communication channel in the occupied country. In a different contribution for The Belgian War Press you will read more on the censored press.

The first ‘prohibited’ leaflets

The Belgian population found it difficult to bear the isolation from the world imposed by the occupier and remained hungry for information on the evolution of the conflict. The censored press, and no more the many rumours that circulated, could provide for this need. Thus, the rare allied newspapers smuggled into the occupied territory sold at high prices. The first clandestine papers or “prohibited” papers that appeared in 1914 largely constituted a solution to this problem. In many cases they reproduced the articles of the allied press. La Soupe, which appeared in Brussels for the first time in September 1944 was probably the most conspicuous and prolific manifestation of this type of clandestine paper. Only a year later, it had succeeded in publishing more than 500 copies, mostly reproducing political declarations. The Revue hebdomadaire de la Presse française (or Revue de la Presse from 1917 onwards) was another, more elaborated example. Founded in Leuven in February 1915, it offered its readers in 3 or 4 issues per month a selection of articles from the major titles of the French press, sometimes supplemented with articles by its own journalists.

A proper national censored press

In the first months of 1915, a second wave of clandestine papers arrived. No longer content to serve as an echo of the international press, they wanted to be the voice of the occupied country. La Libre Belgique was without doubt the most famous and probably the most representative newspapers of this second category. Its goal was to express and orient the state of mind of the occupied people by counterbalancing the demoralisation of the population caused by the censored press. In spite of several waves of arrests, the catholic Brussels paper succeeded in publishing 171 copies between February 1915 and November 1918, of which certain had a circulation of more than 20,000 copies distributed in nearly all of Belgium.

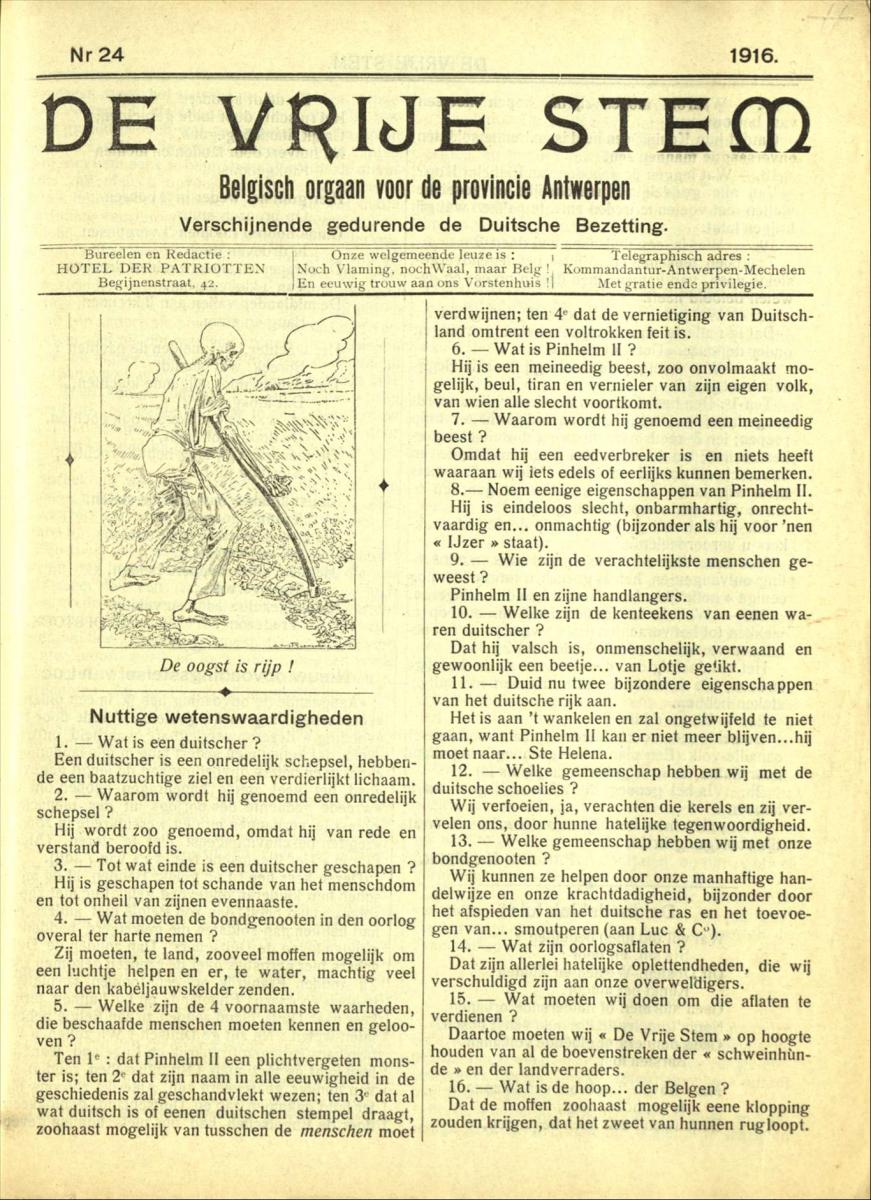

The success of La Libre Belgique was however exceptional. Most of the 77 known clandestine papers that appeared during the Great War were only published for a short period and with a limited circulation. Titles such as L’Âme belge, La Revue de la Presse, De Vrije Stem or De Vlaamsche Leeuw did succeed in circulating during most of the occupation period, even if their numbers were not as high throughout the country as the ones of La Libre Belgique.

The struggle against the pro-German press took a peculiar turn in the north of the country where the Flemish movement founded several “passivist” clandestine papers. Droogstoppel and De Vrije Stem, De Vlaamsche Wachter, and also De Vlaamsche Leeuw aimed at constituting a counterbalance against the activist censored press, which they considered an insult to the Flemish case.

The censored press examined

The Dutch-language clandestine papers were less numerous then their French-language counterparts: 14 Dutch-language titles and 2 bilingual, against 51 French-language titles. The statute of French as official language goes some way in explaining this, but the geography of the occupation probably also played a role. The censored press was indeed very rare in the lines of communication area. The occupation regime was particularly draconian in this area, which covered more territory in the Flemish part of the country than in the francophone part. In fact, the majority of the clandestine papers appeared in the territory of the Generalgouvernement Belgien, in particular in Brussels and in a lesser degree in Antwerp. Also remarkable is that the development of the clandestine press occurred mainly during the first part of the occupation. The repression, the material difficulties and the fatigue of the war contributed to the decline of the phenomenon from 1916 onwards.

Emmanuel Debruyne