Censored Press in World War II

The German occupation of Belgium put an end to the basic, constitutionally guaranteed, freedom of the press. Immediately after the German invasion, Belgium was subjected to a system of press censorship by the occupier, initially as a precautionary measure. In the autumn of 1940, an a posteriori censorship was introduced. Because this system proved not to be fully secure, a preventative censorship was reintroduced in August 1942. Furthermore, a newspaper could not be published without the authorisation of the occupier.

The occupier controlled everything

The military government also employed other means of controlling the press, such as the centralisation of news gathering, the establishment of a monopoly on the distribution channels, the obligation for journalists to join an official professional association and the control of the distribution of paper. The pre-war press agency Belga was put under German control and became Belgapress. All the newspapers had to take a subscription to it thus allowing the occupier to control the news influx. The only way for a newspaper to reach the shop was via the distribution firm Dechenne, equally controlled by the Germans. A photographer or a journalist who wanted to exercise his profession needed either permission to do so or had to be a member of an official professional association. Finally, the distribution of paper was also controlled by the Germans. The Propaganda-Abteilung, a department of the military government, was the most important body to control and censor the press, but the German embassy in Brussels, the Wehrmacht and the Sicherheitsdienst also played a role in the Gleichschaltung of the Belgian press.

Newspapers continued to be published

From the beginning of the occupation to the liberation, 35 titles were published. A number of them only appeared for a few months or years. The censored press was subdivided in three main groups: the press of the collaborationist parties and movements; the independent daily press and the ‘stolen press’. The first group consisted of newspapers that were the official organ of collaborationist parties and movements such as Volk en Staat (VNV), Le Pays Réel (Rex) or De Gazet (Devlag). To the group of the independent daily press belonged those newspapers that had reappeared after May 1940, whether or not with a new title, and that were not the official organs of a collaborationist party or organisation such as De Dag or Le Courrier de l’Escaut. A number of ‘independent newspapers’ were new titles, with an outspoken New Order profile such as Le Nouveau Journal or Het Vlaamsche Land. ‘Stolen’ newspapers are those newspapers that had reappeared without the consent of the owners, such as Le Soir and Het Laatste Nieuws.

In spite of everything, a great public success

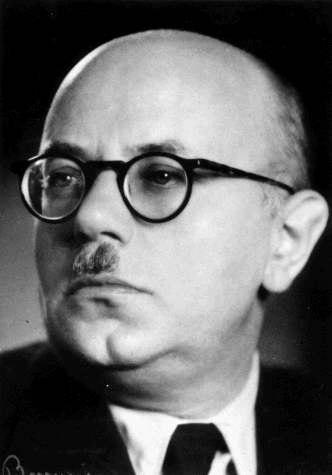

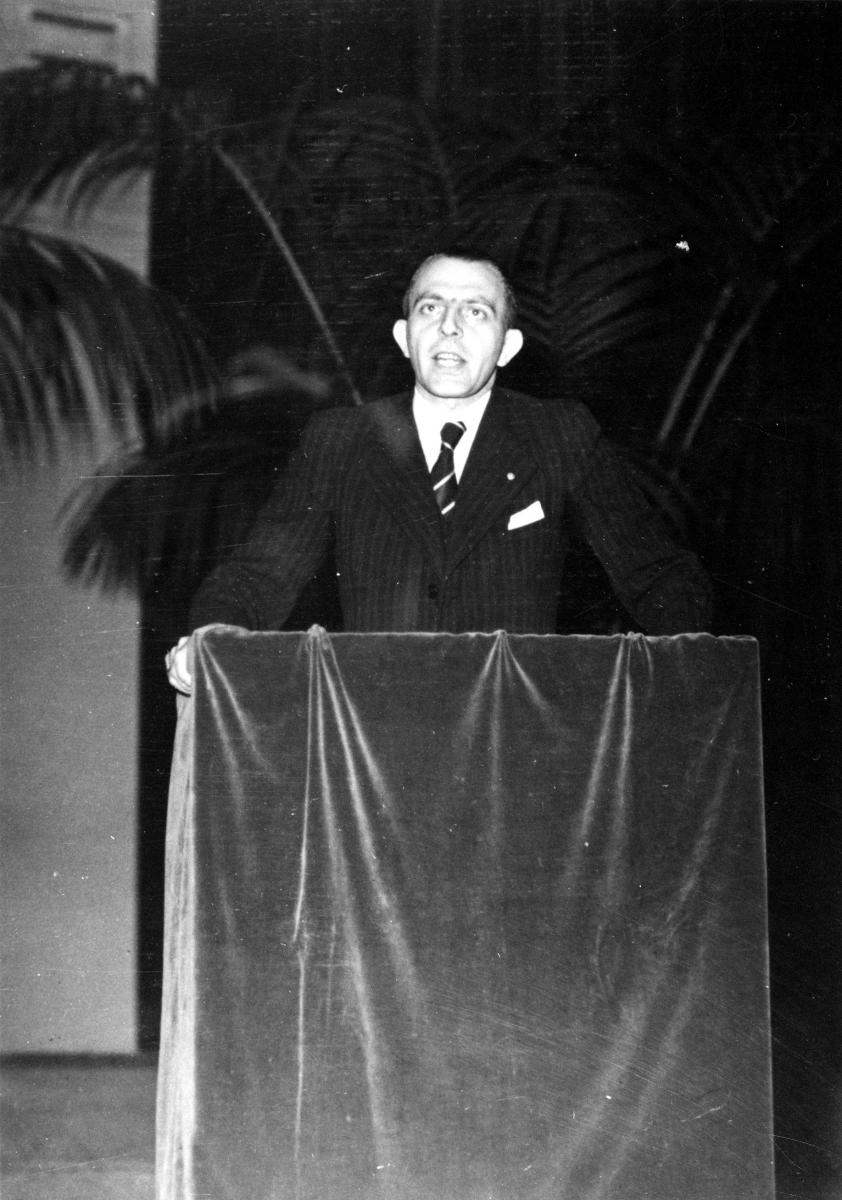

The censored press was a great success and in many cases also a lucrative undertaking. Circulation figures were high and often equalled pre-war figures, taking into account that there was often a discrepancy between the circulation figures and the number of newspapers sold. Of the Brussels newspapers such as Le Soir and Het Laatste Nieuws more than 200,000 copies were printed daily. Most newspapers had circulation figures of 40 to 70,000 copies. In general, the strongly coloured press of the collaborationist parties and groups was less successful and all in all, after 1941, interest in the censored press declined. The appeal of the censored press is generally explained by the informative value of the newspapers. For instance, there was a real need for information concerning provisioning, and the call for diversion and distraction of the readers was a need to which the newspapers gladly anticipated. In contrast, news coverage of domestic and foreign politics was, because of the strict control of the occupier, much more streamlined and stereotype. The censored press also had a strong symbolic and political significance as appears from the deadly attack by the Resistance in April 1943 on Paul Colin, the founder of Le Nouveau Journal.

Bibliography

- Alain Colignon, ‘Première page, cinquième colonne’ in F. Balace (ed.), Jours de guerre/Jours Noirs, Bruxelles, Crédit Communal, 1992, p. 7-32.

- Els De Bens, De Belgische dagbladpers onder Duitse censuur (1940-1944), Kapellen, De Nederlandsche Boekhandel, 1973.

- 'Presse de collaboration (langue française) – Presse de collaboration (langue flamande)' in, Paul Aron, José Gotovitch (eds.), Dictionnaire de la Seconde Guerre mondiale en Belgique, Bruxelles, André Versaille, 2008, p. 345-350.

- Roel Vande Winkel, 'Gelijkgeschakelde stemmen : officiële informatiemedia in bezet België, 1940-1944', in, Tegendruk. De geheime pers tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, Gent, Brussel, Antwerpen, Amsab-ISG/SOMA-CEGES/Erfgoedcel Stad Antwerpen, 2004, p. 49-66.

- Rudi Van Doorslaer, 'Ulenspiegel: Een kommunistisch eksperiment met een Vlaams-nationale legale oorlogskrant Antwerpen: 5 januari 1940-1 maart 1941' in, Wetenschappelijke Tijdingen, 1975, 34, 2, p. 93-94.